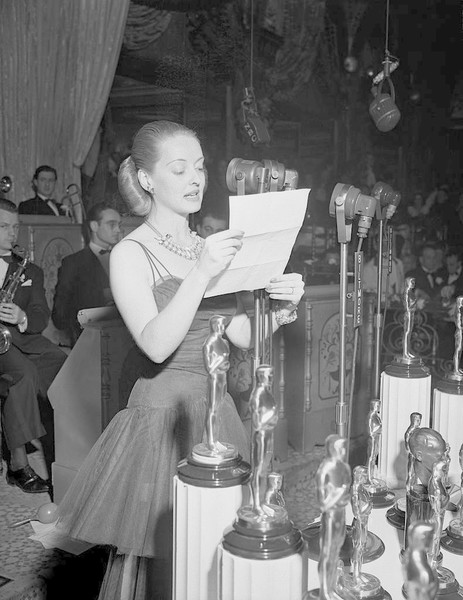

Bette Davis had recently resigned as

President of the Academy. In 1941, the 33-year-old assumed Hollywood's

top job, proposed doing away with dinner and dancing at the Oscars and

revoking the right of extras to vote — ideas that were later implemented

— and was met with such great resistance that she stepped down after

less than two months.

Davis

hadn’t made it in Hollywood on her looks. She was smart, talented and

suffered no fools, earning her the reputation of being “difficult” — and

numerous contract suspensions — at Warner's, and it wasn’t long before

the Academy’s board discovered her no-nonsense side. “At the first

meeting I presided at as president. I arrived with full knowledge of my

rights of office. I had studied the by-laws. It became clear to me that

this was a surprise. I was not supposed to preside intelligently.”

She

had two big initiatives she immediately pushed to enact. First, she

wanted to reformat the annual Academy Awards banquet. Since her

election, Pearl Harbor had been attacked, thrusting America into World

War II and prompting calls for the cancellation of the Oscars, which had

theretofore centered around dinner and dancing. She argued that it

would be more appropriate to scrap the dinner and dancing and present

the awards in a large theater, charging at least $25 a seat and donating

the proceeds to war relief efforts. “The members of the board were horrified,” she later said. “Such an evening would rob the Academy of all dignity.”

Her

other idea was to revoke the right of Hollywood’s thousands of extras

to vote for the Oscars. She argued that many of them lacked taste,

culture and “didn’t even speak English” — and besides, there were

indications that their votes could be swung behind whichever studio

hired them around the time of balloting. Davis later said the board

regarded this as “the wildest thing they’d ever heard” and Wanger, now the first vice president, spoke up and “wanted to know what I had against the Academy.”

Davis quickly realized she was getting nowhere. “It was obvious that I had been put in as president merely as a figurehead,” she later wrote. “I sent in my resignation a few days later.” The Academy tried to keep the news from leaking while Zanuck, her sponsor, tried to run damage control. “He informed me that if I resigned, I would never work in Hollywood again. I took a chance and resigned anyway.”

Her resignation was “regretfully accepted” by the board at its Jan. 7 meeting. The real reasons for her exit were kept largely under wraps at the time. THR reported that it “was predicated upon her feeling that the presidency of the Academy is a ‘full-time job’ which she did not feel she could fulfill in addition to her picture contract with Warners. Additionally, Miss Davis is not in robust health, and the performance of the titular Academy office would require an endurance which her doctors felt she did not possess.”

Wanger re-assumed the presidency, and two months later the 14th Oscars took place, still as a dinner, but minus dancing and formal attire, and with attendees asked to support the war effort. Extras retained the right to vote, which almost certainly tipped the scale in the best picture race against Citizen Kane, to the Academy’s eternal embarrassment. Within just a few years, though, the Academy had implemented both of Davis’ big ideas: the 16th Oscars were held in a theater, as has been every installment since, and extras lost the right to vote ahead of the 19th Oscars.

Davis, meanwhile, far from faded away. She was nominated for three more best actress Oscars before the end of the war, and spent most of her spare time supporting the war effort — she sold millions of dollars in war bonds and started the Hollywood Canteen to entertain servicemen on leave. She and Zanuck didn’t speak again until nine years had passed — “Because he had strongly recommended me, I’d embarrassed him,” she acknowledged — but they reconciled after he cast her in the greatest film of her career, the best picture Oscar winner All About Eve.

Late in life she confessed that she regretted abandoning the presidency of the Academy rather than staying and fighting for her ideas. “I resigned the position in order to show them, but then nobody cared. It’s usually a mistake doing something just to show someone. If I couldn’t function, if my suggestions were disregarded, why should I bother? They wanted a mere figurehead, someone famous to publicize the Academy. I didn’t know that. I wanted to rule.”

No comments:

Post a Comment